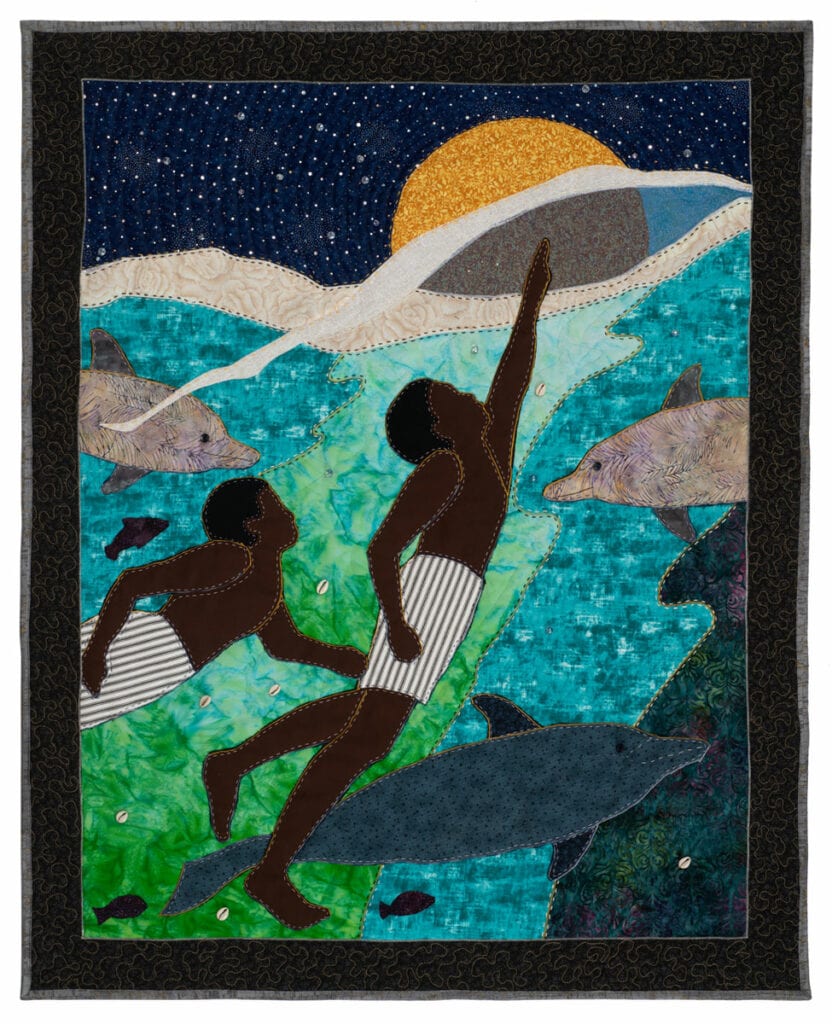

In an interview published this month in BMoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas, artist Stephen Towns discusses his collection of quilt work from A Songbook Remembered, a series that portrays imagined historical narratives with imagery drawn directly from the poetry of African American spirituals, with Teri Henderson. De Buck Gallery showcased works from this series in a show of the same name from October to November in 2020.

Towns is a painter and fiber artist working primarily in oil, acrylic and quilting. His work explores the African Diaspora and how American history influences contemporary society, in direct response to issues that have affected African-American culture–issues such as loss of ancestral roots, slavery, class, education, skin tone and religion. The subjects in Towns’s works are not only glimpses of the sitters; they are also a reflection of himself and mirror his struggle to attain a sense of self-knowledge, self-worth and spirituality. This quilt series celebrates the aesthetic traditions of African American women while exploring America’s history of slavery and labor. The quilts speak to how fabric preserves memory, both in Towns’ often deeply personal connection to his materials as well as through the narratives he depicts of historical African Americans.

This insightful conversation explores Towns’ background, his inspirations, and how culture and spirituality are in dialogue with his artistic practice. Read excerpts below:

Teri Henderson: The first time I saw your work in real life was the Rumination and a Reckoning show at the Baltimore Museum of Art. I’d been in Baltimore since 2016, that show was in 2018, and it was the first time I had seen work here that felt more familiar to me. It resonated with me—it was very Black, very Southern, and I loved the elements of the Black church. So I wanted to talk about how Southern culture and Black church traditions are illustrated in your new show, A Songbook Remembered.

The funny thing is that I didn’t have the Black Southern church experience. I grew up as a Jehovah’s Witness. There’s no holidays and the concept of Jesus is a little bit different. When I went to college in the late ’90s and early 2000s, that’s when I started that journey of visiting different churches. And that was when I was finally away from home and I could explore the church experience, and it was a Black church experience. In the beginning, to be completely honest, it was scary for me. That was the first time I saw collection plates and people falling on the floor catching the Holy Ghost. It was scary and that was the first time that religion felt like magic.

When you grow up as a Jehovah’s Witness, a lot of the focus is on God and not on you. And on the importance of being a human being, one of God’s beings, instead of God being this big figure. So, when I started making work, I started by painting Black people with gold halos. It was to show the godliness and the beautifulness inside of us. I started with searching and exploring through that.

It evolved from that in just going through all the troubles of 2020, like being depressed and unable to make work. All the news was bad. So I had to find a way to feel good, and with these spirituals, I was able to find a new language to overcome these obstacles. Because, I mean, if people can come from slavery and overcome those obstacles, then I could overcome these things through 2020 because I came from those people.

What has your artistic practice included this year? Have you been quilting and painting?

This year it’s mostly been quilting. It’s been sort of a new medium. It was the thing I could get and use, because a lot of the times when I’m painting I need a mask, I need gloves, I need all of that stuff, and all of that stuff ran out during COVID, so I couldn’t buy the things that I needed for my painting. So I had to do a lot of quilting because a lot of the PPE and the stuff that I needed I couldn’t find. And then it all raised in price and it was very expensive. Now I’ll be able to paint and use the equipment that I used to use, because now you can find some of that stuff in the store, but before you couldn’t find that stuff earlier during quarantine because it was all being snatched up.

When did you start working on A Songbook Remembered?

Sometime in June. There was a period right when COVID started where I just stopped working just because the news was bad, and I was depressed. I could not get myself to make work. And then A Songbook Remembered was this body of work with this new sort of thinking that motivated me to start working again. Which is good. It was the spirituals that helped me through this time.

What is your favorite spiritual?

“Wade In The Water” is very common and there are so many versions of it. But I love the song “Deep River,” especially the melody. There’s a famous recording that Marian Anderson does at either the Lincoln Center or Lincoln Memorial. That melody is one of my favorite ones.

What are some of the most common symbols or references in your work?

I always use a lot of fish. They represent Jesus [for example, in the Biblical story where he performed a miracle of feeding the multitudes with five loaves of bread and two fish]. I remember in the early 2000s, the Christians always had those fish necklaces, they had the fish bumper stickers, the rings. A lot of times, the way I’m thinking about my composition, I use triangles. Triangles are sort of, for me, representing the Holy Trinity, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. A lot of times when you see that in my work or notice it, it’s not overt until I tell people, and then they’re like, “Oh, I see the triangles.” I incorporate them a lot into my work.

What are some of the source historical patterns or fabrics that you use in the show?

A lot of it just comes from my stash and then a lot of it comes from this store called SCRAP Creative Reuse that I shop at for used fabrics. Because they have become so familiar with me, they can become familiar with my style, and if somebody comes in, they may say, “Oh, we have something that was just donated. You might like it.” Since I am doing work in a particular style, a lot of the patterns that I try to get are not really available now. So I rely often on things that people give away and things that I can find in estate sales and stuff. This sort of goes back to praying—it’s sort of morbid, but a lot of this relies on people dying. Somebody’s grandma or meemaw dies and they have this fabric stash and they donate it because they don’t know what is going to happen. A lot of times when that stuff comes in, I will say a prayer for that person and thank that person, because they didn’t know that throughout their life, they were getting the materials just for me to make this work.

What is the show about?

It’s basically going back to spirituals, and finding the hope and resilience in spirituals, and creating a language for how to navigate 2020 and all of the troubles of 2020. The thing I read about spirituals is that they were used as protest. They could be religious or they could be used as protest songs, these songs of being free and people singing who weren’t free. All of this [making this body of work] took place during the Black Lives Matter protests over the summer. So all of that stuff was being processed in this work when I was making it.

I know that historical figures like Nat Turner and Harriet Tubman had previously shown up in your work. Are any of them depicted in this series?

In the piece “Go Down Moses”—it’s the piece with the woman basically as Moses parting the Red Sea—that’s me using Harriet Tubman as Moses, because she was called Moses. She just keeps coming up in my work. I’ve been able to read about her and learn about her life. I’ve seen things that happened in her life sort of happening now and the important things that she helped change. She is such an important figure in history.

Towns currently lives and works in Baltimore, MD. In January 2022, Declaration and Resistance, a solo exhibition of paintings and quilts, will open at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Pennsylvania.

To read the full interview, “Triumph in the Face of Terror: African-American Spirituals and Stephen Towns,” please click the link below.