~

Timed with Her Spotlight Presentation, De Buck Gallery Sits Down with Artist Emilie Stark-Menneg to Dive Deep into Her Most Recent Body of Work

~

De Buck Gallery: If you had to pick a prompt for this series of works, what would it be?

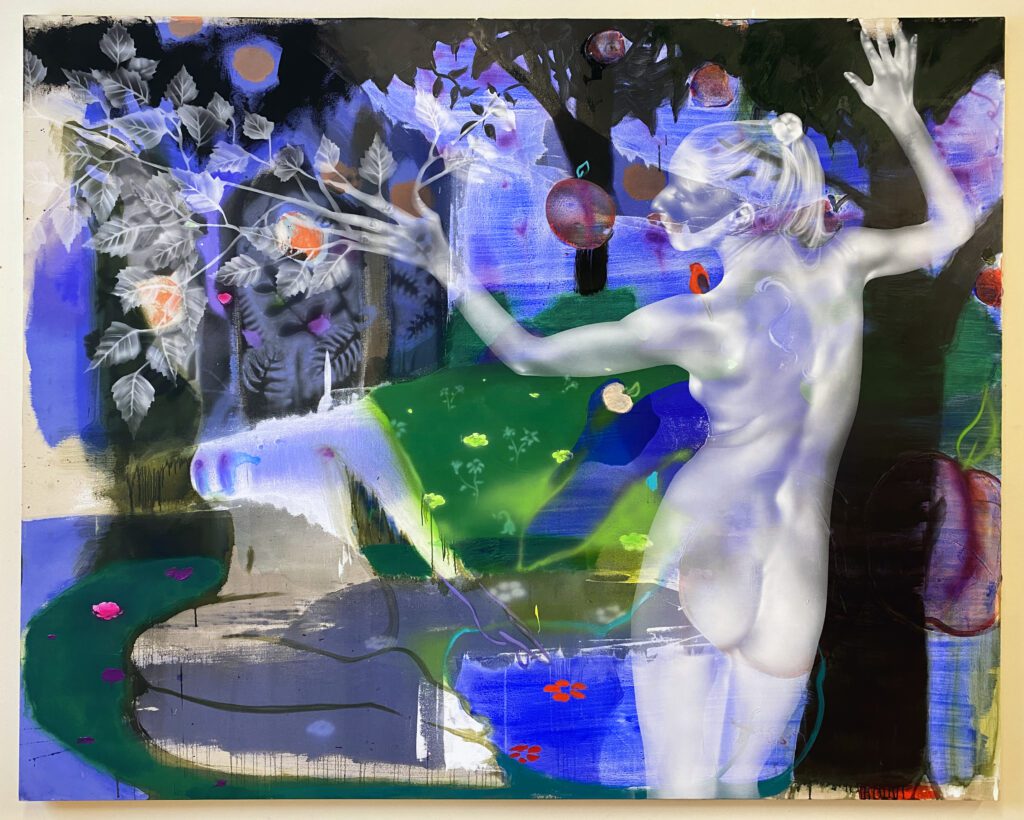

Emilie Stark-Menneg: There’s a particular piece that Ana Mendieta made where she is lying in the ground, she has these incredible blossoms springing from her body. Ever since I was a kid, that piece has just been so moving to me. The idea of both life and death in this circle, and the kind of transformation of the human body into all these other kinds of life forms. I’m just constantly sort of thinking about: How do we become?—as a prompt. So with this series, the one that I’m thinking about as the kind of starting point for them is the work Primavera where there’s a figure and her arms become the branches and there’s this kind of possibility of a magical transformation. How that happens is a thing that I continually want to investigate.

There’s also a video by Pipilotti Rist which I continuously return to. It’s the one where there’s a woman strolling down a street and she’s got this giant flower and she’s smashing car windows…. But she’s also very feminine, she has this dress on and these high heels…. I just love that there’s a kind of epic joie de vivre in it and also a vandalism to it, which I think is really interesting, a subversiveness and the destruction of property, but all within the confines of an art piece. Something about that is also what I’m trying to get at in this work, which is the persistence to thrive, or a kind of shattering of structures. A shattering of language, I think, painterly language, is happening in terms of the layering.

DBG: You have written, “Whereas, figurative painting often posits the body in terms of persona, performance art often presents the body as a conduit, a passageway between states of absence and presence.” Your work features some of what appears to be self-portraiture. How does that work? How is that different from the way someone might paint a portrait if they’re thinking of it in a more traditional way. Are you in a performative state when you’re painting yourself?

ESM: That’s where I come back to this idea of it being more connected to performance art. When I’m in the process of making them, I’m sort of imagining the situation, then I get into the poses and I almost feel like it’s a process of dancing or becoming the shapes in the paintings. It’s the process of making a video or a photograph that then gets translated into a painting.

DBG: Your work has many layers to its process, and is sometimes not even related to the canvas. Could you expand on your process?

ESM: Even when I’m working with other people, it’s all very choreographed and improvisational at the same time and involves, usually, multiple studio visits where I’m photographing them and we’re talking through these kind of fantasy situations of like, “What would—or where do you think you would be transforming into” or “What kind of space would you love to travel into in this painting?” There’s this kind of conversation that’s happening. Almost like a conjuring. Then I’ll do sketches and paintings from both life and from the photographs. So it all gets woven into it.

“I just love that there’s this kind of epic joie de vivre and also a vandalism to it, a subversiveness and the destruction of property, but all within the confines of an art piece. Something about that is the sort of thing I’m trying to get at in this work, which is the persistence to thrive, or a shattering of structures.”

DBG: Your work seems to border on the figurative and the abstract—such as Strawberry Unicorn. Is there a difference to you between working in the abstract versus the figurative?

ESM: In all of these paintings, I actually saw them very clearly as figurative work, and I was totally surprised when I had other viewers see them completely abstractly, which I loved! But it was this question of, “How is what I’m seeing and what other people are seeing so different?” I started [Strawberry Unicorn], based on a Henry Moore sketch that I loved. It was this woman riding a horse. What I can’t remember is if I had seen the Henry Moore drawing first or if I saw the unicorn in this painting first. But there was this wonderful moment, and I think in all of them, where the image just kind of arrives in this magical alchemy of paint going everywhere. What’s interesting about working on the floor on canvas is that the canvas reacts to the gravity and so the paint will pool in the center and travel in ways that I have no real control over. There’s a lovely sense of surprise and energy and call-and-response.

DBG: You say Henry Moore was an inspiration for Strawberry Unicorn. Are there any particular inspirations behind the other works in this series?

ESM: [Wild Blueberries] is a painting that I tried to make so many times. I think because it comes from lots of different places, but one of the places that it comes from is Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which I saw as a very young person. There’s one young woman who eats a blueberry or eats one of the candies and she turns into a blueberry. As a kid, I was terrified, but I also couldn’t look away. I was like, “Whoa, here is a transformation happening.” I’m trying to deal with that simultaneous fear and thrill of becoming something else. I think that definitely ties into mortality in terms of thinking about life and death and how we decompose and compose.

DBG: These references between both Primavera and Wild Blueberries evoke this image of Adam and Eve with the Forbidden Fruit and this idea of a landscape that teeters on good and bad. Is that in some way related to your prompt?

ESM: I’ve been thinking about Adam and Eve a lot and I don’t think I’ve addressed it in paintings. I was thinking of the Michelangelo version where there’s such a sense of shame as they’re being thrown out. I’m looking at the blueberry painting and I think there’s got to be something going back to that [sense of], oh you can’t eat this fruit, and if you do, you’re going to get expelled from this garden. So it’s like, “Well, let’s eat all that fruit” because I love the idea of doing the opposite of what I’m being told to do.