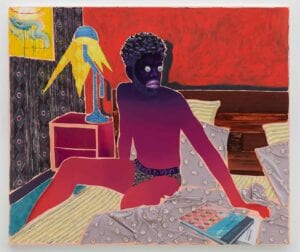

Devan Shimoyama, Midnight Rumination, 2019

A reading list for black futurity—what might it contain? The paintings in Devan Shimoyama’s “Shh…,” a small recent show at De Buck Gallery in New York City, offer some recommendations. Each of the six large glittering collages, painted in oil and acrylic and adorned with the artist’s signature rhinestones, sequins, and fabrics, shows a lithe harlequin figure with bejeweled, searching eyes. Some are self-portraits or portraits of friends and acquaintances, others are completely out of Shimoyama’s imagination. All of the figures are portrayed with books by various writers in everyday spaces made spectacular with a liberal use of glitter and costume jewelry that give texture to the scenes’ surfaces. In Baskets Yet to Be Woven (2019), a young woman sits cross-legged in an armchair in front of a set of windows framing a purple storming sky. Her feet are high-key yellow and her head is red-hot, suggesting how, Shimoyama told me, “temperature zones in the body” might react to the black feminist educator Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s M Archive: After the End of the World, which rests on a tiny table beside her. The book is the second installment of a speculative, afro-pessimistic fiction trilogy that follows a future researcher as she unearths the ills of late capitalism, global warming, and anti-black discrimination while examining possibilities of living beyond what had previously been known of the human condition.

In other paintings, we see readers studying Octavia E. Butler’s Bloodchild and Other Stories, Roger Reeves’s poetry collection King Me, Mark Godfrey and Zoé Whitley’s exhibition catalog Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, and Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. Together, these books represent a sort of new-age bibliography that tackles race, gender, and being to present histories of humanity, rewritten. In creating images of the black reader in pursuit of radical pedagogy and fresh ideas, Shimoyama critiques the historical narrative of painting and literature, in which the official canon of the humanities is based on the books and artworks of mostly white creators. The paintings in “Shh…” are a departure from the work that Shimoyama has made over the last six years, some of which was displayed recently in his first solo museum survey, “Cry, Baby,” at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, where he lives and is an assistant professor of art at Carnegie Mellon University.

The queer Trinidadian-Japanese Shimoyama was born in 1989. He grew up in Philadelphia and received a master’s degree in painting and printmaking from the Yale School of Art in 2014. The Warhol show focused in part on his campy mythological self-portraits, such as Daphne (2015), in which he appears as the minor Greek goddess in a palette of greens and with eighteen eyes. In the myth, Daphne was the master of her own fate, metamorphosing into a laurel tree to escape Apollo’s sexual advances; in Shimoyama’s painting, he recasts himself as the nymph to show desires for the queer black body that elude the presumptions of the heterosexist gaze. Shimoyama’s lush, surreal compositions—such as He Loves Me (Not) (2016) and Butterfly Eater (2017)—conjure up the oeuvre of Chris Ofili; they also bring to mind the deeply imaginative and intimate black worlds in the recent drawings of Toyin Ojih Odutola and paintings of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

But Shimoyama’s use of parable and allegorical symbols—snakes, teardrops, flowers—has often been more explicitly political. He has made paintings and sculptures that memorialize black victims of police brutality; and in his continuing series of “Barbershop” paintings, begun in 2017 and displayed at the Warhol Museum, he explores intersections of queerness and blackness in what he refers to, in an interview with Emily Colucci in the Cry, Baby catalog, as the “more realistic spaces of barbershops” but here imbued with elements of magic, mystery, and glamour. In Finesse (2017), a purple, black, and gray male figure sits in a barber’s chair wearing a smock fashioned out of dark boa feathers. He is crying pear-shaped-diamond tears as he gets his hair faded with clippers attached to a serpentine cord made from a beaded necklace. The anonymous hand that styles his hair is feminine, with long, burnt orange fingernails. It’s the barbershop reimagined as a space where masculinity emotes and embraces vulnerability. Materially the portrait recalls Mickalene Thomas’s rhinestone-studded collages, which express a jubilant queer black womanhood. However, Shimoyama told me that his work speaks to the tension he has felt, given his sexuality, in the black barbershop, a traditional haven of hyper-masculinity where he has experienced both beauty and alienation.

Shimoyama’s “Barbershop” paintings provide a contrast to Kerry James Marshall’s De Style (1993), a salon-style painting of the African-American barbershop. Jessica Beck, the curator of Shimoyama’s Warhol show, writes in her catalog essay, “Devan Shimoyama: Exploring the ‘Self’ in Self-Portraiture,” that the figures in Marshall’s painting are made with “honor and grace” in a space filled with symbols—a tiny picture of a boxer, a calendar featuring the female anatomy—that has served to isolate queer boys and men like Shimoyama. Most critics and art historians have seen Marshall’s painting as restoring glory to the black body, but Beck offers an alternative read: “This space also appears to operate according to social norms that require men to wear their masculinity proudly” in what is not a universal sentiment of harmony. For Beck, “Shimoyama’s barbershop makes a similar use of signs and symbols, but focuses instead on young men—boys who cry in their isolation. Their tears…come from the fear of being outed, shamed, or judged for their failure to perform the masculinity that Marshall’s figures so comfortably embody.”

Shimoyama’s impulse to complicate conventional notions of masculinity is also visible in the paintings of readers that were included in “Shh…,” the recent exhibition at De Buck. The opening painting, A Man and a Brother (2019), shows a male figure standing alone in a living room, wearing blue denim shorts with yellow, green, and pink flowers covering his legs and arms. Tacked to the wall behind him is a poster that features the popular Civil Rights Movement declaration “I AM A MAN.” He is holding Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, an experimental book-length poem about anti-black racism encountered in the form of daily microaggressions, which won the 2014 National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry.

A close reading illuminates the connection between A Man and a Brother and the lone sculpture in “Shh…,” which might otherwise feel out of place. It’s a beautiful homage to Trayvon Martin, a black youth killed in 2012 by a white vigilante, in the form of a cotton hoodie decorated with silk flowers, sequins, and glitter. The construction of the sculpture recalls the spontaneous memorials that pop up on urban street corners after tragedies. It’s titled February II (2019), the month Martin was born. Rankine’s text, as well as the cover of her book—illustrated with a picture of David Hammons’s sculpture In the Hood (1993), consisting of the severed hood of a sweatshirt—speaks to the circumstances of Martin’s death and the title of Shimoyama’s living room scene, evoking the precarious duality in which black men and women live: always asserting and reasserting their personhood, in the most unlikely of places that could end their lives.

In Shimoyama’s newest works, desire is present, expressed in a wish “to play creator, to construct new individuals,” he explained to me. The series began last year with Black Gentleman (2018), a painting of a black male hued in gradations of brown with ornate flowers for eyes, sitting on the floor reading Boy with Thorn, Rickey Laurentiis’s debut collection of poems, which traces the writer’s rich and religious gender-queer biography. The book’s cover is printed on paper and pasted to the canvas as a kind of totem. Its considered placement carries a prominence generally reserved for the figure in portraiture, and it provides a counterpoint to the race and gender norms that abound in our culture, moved symbolically by the painter from the margins to the center .

Laurentiis’s volume of lyric poetry makes another appearance in Miles (2019), where it is tucked away on a shelf behind a multicolored figure, sitting with a hand on his cheek, his starry gaze fixed directly on the viewer. The pose is one of resignation, and it alludes to the opening stanzas of Laurentiis’s poem, referenced in Black Gentleman, the earlier 2018 painting that bears its name, about the stereotyping of black identity. Laurentiis writes:

There are eyes, glasses even, but still he can’t see

what the world sees seeing him.

They know an image of him they themselves created.

He knows his own: fine-lined from foot to finger,

each limb adjusted, because it’s had to,

to achieve finally flight —

though what’s believed

in him is a flightlessness, a sinking-down,

as any swamp-mess of water I’m always thinking of

might draw down again the washed-up body

of a boy, as any mouth I’ve yearned for would take down,

wrestler-style, the boy’s tongue with its own …

In the painting Maladai (2019), which was on view in “Shh…,” a woman stands at a bus stop at sundown intently devouring Tananarive Due’s 1997 mystery novel My Soul to Keep. It seems that what Shimoyama wants us to think about is what we might be able to control of our identities and our realities by considering and creating language, both visual and written, that defies established representational paradigms. Outside the galleries of portraiture, progress—albeit not enough—is affecting the world of art and literature: museums and publishing houses have already begun creating an alternative contemporary canon that not only takes as its theme the survival of black subjects, but also imagines their futures, and finds within their lives the full spread of pleasure, beauty, and abandon. What is becoming legible is how this subtle resistance to the status quo—the premise of Shimoyama’s canvases—is challenging the old ways with an eye toward what will be possible in time to come.