As a young, black kid growing up in a predominately white neighborhood in Philadelphia, Devan Shimoyama first remembers hearing the term “sweet” being used in a positive context.

“The term ‘sweet’ had been used by white friends as something more like ‘cool’ or ‘awesome,’” Shimoyama told NBC News.

It wasn’t until Shimoyama went on to middle school in a different neighborhood that he noticed a change in how the word was being used by those around him.

“I had never been around so many other black boys and girls and recall the term being used towards me in a derogatory way,” he said.

Shimoyama, who identifies as gay, said he would especially hear the term thrown at him in gym class when he didn’t excel in basketball, or used against him because of the way he walked or talked.

“That’s when I knew there was a shift in the meaning of that word in this new context,” Shimoyama said.

Eventually, the young student learned to stay quiet and assimilate into what he described as a more heteronormative ideal of masculinity — all in an effort to protect himself from being called “sweet” by his classmates.

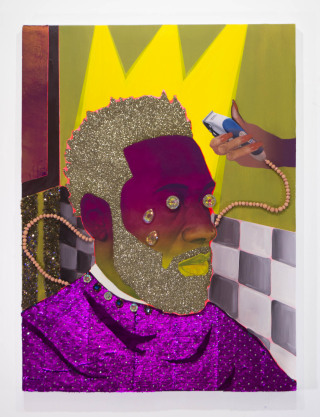

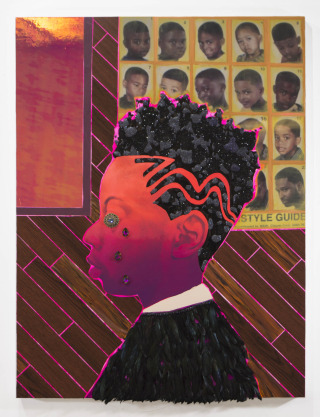

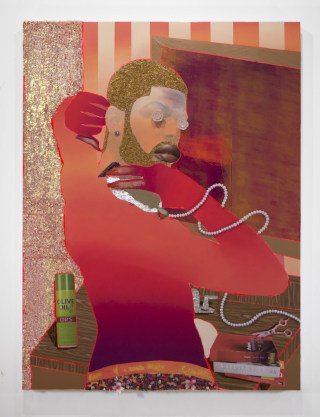

Titled “Sweet” and on display at New York’s De Buck Gallery until December 9, the series of paintings and mixed media art pieces were inspired by conversations Shimoyama had with other gay black men about their experiences in black barbershops. These conversations helped allow the artist to reimagine the familiar setting into a space more inclusive of queer and transgender individuals.

“Much of my work prior to ‘Sweet’ explored my identity as a gay black man, but through the lens of a more fantasy, folklore, mythological, narrative approach,” Shimoyama explained. “Now, I’ve made a transition into representing the black gay male in a more actualized familiar space, in which most heterosexual black men look to as a safe space to convene and decompress and talk candidly with one another.”

But Shimoyama said the fraternal bonds and discourse often formed in barbershops doesn’t always allow room for queer voices. “The black barbershop is not quite [a safe space] for gay black men or women, as it is hyper-masculine and heteronormative and at times homophobic,” he explained.

Shimoyama said he has friends who have been turned away from or treated poorly in barbershops for being too feminine, and he himself has heard other men using homophobic or misogynistic language in in these spaces. He also said he has seen fathers reprimanding their children for crying or displaying effeminate behavior.

In “Sweet,” Shimoyama envisions a barbershop where queer people can be more open in their identity without the need to mask their queerness. He creates a safe space where all people are celebrated, regardless of sexual or gender identity. But Shimoyama is quick to emphasize that he is not trying in any way to vilify the idea of the barbershop or those who seek community there.

“I instead sought to construct my own fantasy, over-the-top, queer, drag, femme barbershop in which black males can truly convene and decompress and cry and express themselves as they truly are,” Shimoyama said.

The portraits are painted with bright colors — reds, yellows and purples — with repeated shapes and patterns. Shimoyama also utilizes materials like glitter, sequins, feathers and jewelry, creating a sculptural and textured feel to the works.

“I’ve come to an understanding of how certain materials function in my paintings, such as the glitter in the hair of my paintings mimics the texture of black hair, [and] the sequined or feathered fabric [serves] as the cape the barbershop clients wear to protect their clothing,” Shimoyama explained. “I think of myself as using similar techniques as drag queens when creating these paintings; they’re adorned, dazzling, celebratory, exaggerated versions of reality.”

Shimoyama’s show also includes two sculptural hoodies put on display — a piece of clothing he says has gained cultural significance.

“The hoodie is a reminder to all black men of the true dangers of how black masculinity can be reduced to this emblematic image and that we need to unite and be kind to one another regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity,” Shimoyama explained.

Though Shimoyama believes artists have the capacity to be activists in the work they create, he said his paintings don’t have the same impact as being out on the streets and picketing, or making phone calls. But he does believe there are opportunities for him to start a discourse with his work.

“When I get a chance to talk about the work in interviews … engaging in community activities and giving panel discussions is where I’m able to be less passive and directly engage with people and make the work even more activated,” Shimoyama explained. “That intersection is where I feel as though I can start to make somewhat of a change.”

Shimoyama said he was heartened by the opening reception of “Sweet” earlier this month at De Buck Gallery, and said it was validating to have individuals come up to him and immediately relate to his own experiences as a gay black man.

“This body of work … conceptually came out of conversing with other black gay men about our experiences in black barbershops,” Shimoyama said. “And being able to meet so many new people who immediately relate to those same experiences expressed in the work felt like the work functioned as a call to a community of individuals who could really understand each other.”

By Kevin Truong