In Stephen Towns Spotlights Workers at Bottom of America’s Economic Ladder, Forbes takes a close look at artist Stephen Towns‘ exhibition at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, “Stephen Towns: Declaration and Resistance,” the recently-opened show which uses labor as a vehicle for examining the American dream through the lives of Black people.

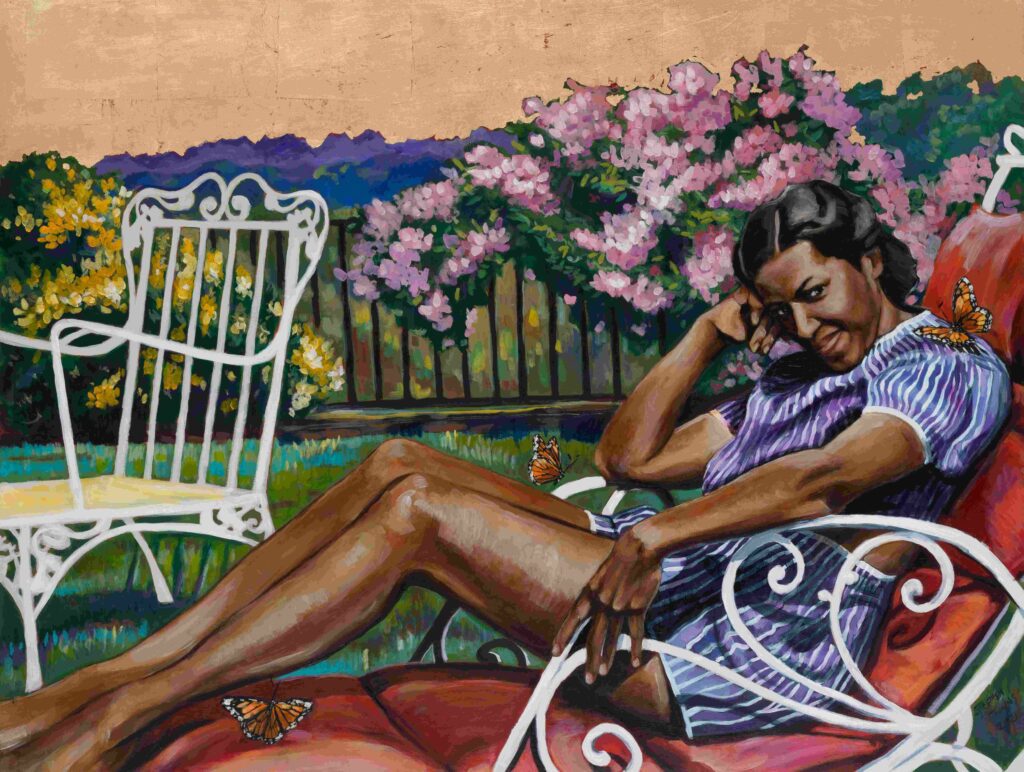

Curated by Kilolo Luckett, the solo exhibition features 35 new works including 27 figurative paintings and eight story quilts, many of them rooted in heavily researched subjects and insights from personal experience. In preparation for his portrait of Elsie Henderson, for example, Towns did a residency at the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Fallingwater, the renowned home of the Kaufmann family for whom Henderson worked. His popular Coal Miners series features Black miners in West Virginia who dealt with the most insecure, underpaid, and often, most dangerous jobs.

Excerpt From the Article:

Working in series, Towns explores industries such as coal mining, agriculture and domestic labor, as well as labor that highlights care and nurturing such as nursing, a theme he felt was important to pursue as he created new work during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighting the racial disparities that continue plaguing the country.

“When you’re working in those positions you can feel disrespected by the people that you’re working for or the people that you’re offering service to, so it was very important for me to tell those stories because I’ve been that person”

Stephen Towns

“This exhibition centers on the lived experiences and contributions of Black Americans, whose labor built this nation,” Anne Kraybill, The Richard M. Scaife Director/CEO of The Westmoreland, said. “With a shared focus on labor, Stephen’s art connects well to our collection, but more importantly, his works reveal stories that have been largely left untold in American history and in American art.”

Stories that, despite their humility, have earned prominent telling.

“I’ve done a lot of (art)work around Black people and slavery and some of the criticism I’ve gotten from other Black people is that I don’t focus enough on the kings and queens or very valuable, important people,” Towns said. “There is a narrative that we come from kings and queens, but I probably didn’t come from a king or a queen, I probably came from a laborer that was captured and sold into slavery and there is just as much importance in the people in the background as there is in the people on the top.”